Detroit to L.A. ✈️

How Dilla's life and death impacted the

Los Angeles beat scene

Presentation for Dilla, Detroit, and Machine Music course @ NYU.

This talk is built around the chapters in my book dedicated to L.A. as well as an unreleased documentary called All Ears, which is I think one of the best documents of the early years of the L.A. beat scene as it came to global recognition in the late 2000s.

I believe Dan shared all these things with you already in preparation for this class so I’m going to do my best to provide a little more context and insight and touch on some things that weren’t included in either though there’ll be some overlap.

Setting the Scene (intro)🥁

I wanted to start off with a little scene setting introduction regarding two key ideas, one that underpins the book and the other that is specific to L.A.

So the book is focused on the intersection of instrumental hip-hop and electronic music and for the longest time I struggled to find the appropriate terminology to describe this intersection.

Photo: Priscilla Jimenez

“It’s the hip-hop element that makes it beats, that’s what beats is, beats is part of hip-hop. To take hip-hop away from electronic music, you wouldn’t have half of the music gear you have right now.”

— Georgia Anne Muldrow

And then in 2019 I spoke with Georgia Anne Muldrow and through her passion and insights she helped me understand how to refer to this intersection between hip-hop and electronic music. She talked of a beat culture. [read quotes]

I feel like beat culture has all the refinement of an institution, beat culture is an institution of [music] production.

So beat culture is the term I like to use when talking about the music that we’re discussing today, because I think it captures a lot of what many of us mean when we talk about beats, hip-hop instrumentals, electronic music, sampling and how they all connect.

And the culture part of the term makes space for a historical element, going back to the beginnings of humanity and giving space to other understandings of music beyond western traditions.

Illustration: Kutmah

Then there is Los Angeles. It's a place that’s hard to put into words but easy to imagine. My approach to L.A. in the book, and in practice, comes from two Angelenos with Irish heritage. One born in nearby Fontana with Irish ancestors, the other born in Ireland and adopted by the city.

Los Angeles may be planned or designed in a very fragmentary sense (primarily at the level of its infrastructure) but it is infinitely envisioned.

The first is Mike Davis, whose book City of Quartz has informed my approach to L.A. and remains an incredible guide for navigating what is a very strange but fascinating urban area. This quote in particular has been a sort of guiding light for me, and has proven to be very relevant in many conversations I’ve had with Angelenos about the city.

Photo: Senay Kenfe

The other is Brian Cross, aka B+, who I assume you already know of. In the early 1990s while studying in L.A., B documented the nascent local hip-hop scene, which eventually became his first book, It’s Not About a Salary.

What’s the establishing shot, where is this?

During that time one of his advisors asked him to define what anchored this research. This was his question.

There was no radio support, very little college radio. The clubs were mostly nomadic [...] My answer was to go off and do this series I called the bedroom photographs. That was because ostensibly, this is where the music took shape. It took shape in people’s garages, in their bedrooms.

And this was B's reply.

Source: It's Not About A Salary

B realized that hip-hop was creating its own dynamic between the public and private spheres in the city.

Source: It's Not About A Salary

These photos then spoke to the idea that in L.A. the bedroom studio was an interface between the public and private, an idea that eventually became central to my book with regards to the rise of what became known as bedroom producers or bedroom musicians.

So these two ideas expressed by Mike Davis and Brian Cross are important to help us understand what came to be known as the L.A. beat scene in the late 2000s:

- Los Angeles as a physical, urban space that is infinitely envisioned by those who inhabit it.

- The bedroom as an interface between public and private, which speaks to a wider idea of the private being where the public is imagined and experienced in the city.

Records and Community 🏠

As for how Dilla fits into of all this, one way into that story is through three different places — two real, one virtual — where his music made an impact before he came to L.A., during his stay there, and after his passing.

Aron's Records on Melrose, circa mid 1980s. Source: Vintage Los Angeles

The first is a record store, Aron’s, which was originally located in West Hollywood on Melrose Ave. You can see the storefront in this photo, which is from the 1980s.

Supporting Local Musicians

And here's a small clip from public access in the late 1980s that explains one aspect of why Aron’s was so special.

Throughout the second half of the 20th century, L.A. was a big record store city and within those Aron’s stood out mainly for the reason that the buyer spoke of in the clip: it was catering to niche tastes and to the idea of an independent mindset back when music — as a fandom and industry — was still defined by a divide between independent and mainstream.

Aron’s offered its customers a range of music united by this mindset, be it second hand records, imports, or releases by local acts. This helped establish it as a favoured digging spot for DJs and producers in the 1990s, full of deep selections at affordable prices and knowledgeable staff who were often DJs, producers, or musicians themselves.

Aron's staff out bowling late 1990s/early 2000s. Source: Facebook

There’s not a huge amount of documentation from that time but here are some photos I’ve managed to collect over the years from people who worked there. This is the Aron's staff on a bowling outing sometime in the late 90s/early 00s.

In-store at Aron's. Source: Facebook

This is from an instore, not sure of the date, it may have been The Roots. Local and (inter)national bands and acts often played at the store.

Daedelus and Take at Aron's, early 2000s. Source: T. Wilson

This is a shot of Daedelus and Take sometime in the early 2000s.

Aron's staff badge, early 2000s. Source: Pay Ray

This was the staff badge.

Anyone who lived in LA in the 1990s shopped at Aron’s and has at least a big stack of records [from there]. I knew damn near everyone in that place. It was like our meeting ground. I’d see you all week [around town] but I could go in there on a Friday afternoon and bump into all my friends.

And here’s a quote from Eric Coleman, B’s partner in Mochilla, speaking to how the store fostered community.

Aron's on Highland, 2006. Photo: Charles P. Everitt

In 1989 Aron's relocated to the other side of Hollywood, off Santa Monica. This is where many of the people in this story first met. It closed in early 2006, around the same time as Dilla passed in fact. This is a photo of its storefront in the last few months.

Aron's, 2006. Photo: Charles P. Everitt

And here is a photo of the experimental section, which was a favorite of many of the producers and DJs who helped birth the beat scene. It was where they’d find weird imports from Europe or records that others weren’t necessarily up on.

Aron’s was key to what would become the L.A. beat scene because it’s where many of its protagonists — artists, DJs, radio personalities, promoters raised on hip-hop and electronic music — first met and hung out.

Another important factor was that record stores were in direct conversation with parties. It was where promoters would drop flyers and spread word of mouth as well as where you'd go to find the music you had heard while out.

As raves and club nights took on a new meaning in America throughout the 1980s and 1990s, this dynamic between the record store and live hip-hop and electronic music was hugely important for local scenes and would last until the late 2000s when the internet began to replace the various communal aspects of the record shop.

Dirty Beats All Night Long 🔊

In the last few years of Aron's existence it became the catalyst for a club night that would in turn give birth to the L.A. beat scene.

Sacred, Kutmah, Frosty (L to R) outside Sketchbook. Photo: Caural

One of the regulars at Aron's was a DJ named Kutmah. He became fast friends with some of the like-minded buyers and shoppers there, including an upcoming producer from South Central named Ras G and staff members Take, Sacred, and Pay Ray.

They all bonded over a love of hip-hop and the desire to find new, unconventional beats no one was fucking with.

In 2004, Kutmah decided to start a club night in a Hollywood dive bar called The Room. He named it Sketchbook and it was dedicated to playing "dirty beats all night long": hip-hop instrumentals, electronic music, dub, and any record that sounded good when thrown in the mix.

If originally in hip-hop they were like, ‘All the strings and all the chorus and all the other shit is bullshit and all we want is the breaks,’ that’s what Sketchbook was for modern music. It was just the juicy, nasty, disgusting bits of music.

Here’s a quote about Sketchbook from Dru Lorejo, who you might know today as one of the people behind the Jazz is Dead label and parties and who back then was an aspiring promoter.

Sketchbook poster.

Residents included Kutmah, Take, Coleman, and Reneau. Kutmah drew posters and flyers and put out sketchbooks on the tables for people to doodle on (hence the name).

Sketchbook wasn’t a club where people came to dance, though that did eventually happen in no small part thanks to the few women who began to regularly show up and help rebalance the dude energy.

Rather it was a place for the heads who congregated at Aron's during the week to get together and listen to their latest finds and geek out. It was an extension of the Aron's experience, and its community.

Sketchbook flyer.

There was an aesthetic those who attended Sketchbook were chasing, an imagining of what beat culture could be at a time when hip-hop and electronic music were still understood as very distinct things.

Because their more famous peers, people like J-Rocc or Cut Chemist, had already locked down digging for breaks or high-level mixing, Kutmah knew they needed to find a space within hip-hop to call their own.

That search led them to scour record bins and new release sheets for music no one was really trying to mess with, beats that felt as fresh as those of Dilla and Madlib from producers close by and further out: Kan Kick, Prefuse 73, Dimlite, Dabrye, Mr. Oizo.

They were trying to take those [beatmatching and mixing] skills to break weird, glitchy, fucked up music that no one was trying to listen to. And that was the geek.

Here’s a quote from Brian Cross that neatly summarises the quest these new heads were on.

Kutmah at The Room (L) and The Little Temple (R). Source: Kutmah, Caural

Here are some shots of Kutmah DJing at Sketchbook in 2004 and 2005.

Eventually they started leaking [those records] at Aron’s, so people got them, but for about three or four months, I was the envy of every Jay Dee freak in the city. That was a great time. It was a competition.

Here’s a quote from DJ Nobody reminiscing about that time he had access to the Dilla and Dabrye "Game Over" collaboration ahead of anyone else in town.

Kutmah at The Little Temple. Source: Caural.

In 2005, Sketchbook moved to another venue, the Little Temple, on the southeastern border of Hollywood. At the same time, dublab also moved into an office space above the club.

An internet radio station founded in 1999, dublab was another key community hub for what would become the L.A. beat scene providing both a physical space with its studio and a virtual one with its internet broadcasts. Kutmah was an early resident on the station and many of the its DJs were also regulars at Sketchbook.

Sketchbook didn’t manifest in a vacuum and there are two other parties in particular that it took inspiration from.

The first is a series of sound clashes organized by the late DJ Dusk in the early 2000s at a club called Gabah, where the Root Down, an L.A. clubbing institution for funk and breaks, was held at the time. Seeing people geek out to producers playing beats on stage was a relevation for Kutmah.

These clashes were documented by Mochilla and this is the trailer. If you’ve never seen the full thing I really recommend you check it out, there’s a full copy on youtube, it’s an incredible document of a moment in time and features many of the people who would become part of Dilla’s L.A. entourage including Stones Throw and the Beat Junkies.

The other party was called Juju, led by the Soul Children, a long standing collective of DJs that Sacred was a part of.

An itinerant party, at the time Juju mainly took place in and around Leimert Park, one of the historical hearts of L.A.'s black community. It was at Juju that Kutmah also realised that you could play beats and people would get down.

Here’s a clip that explains a little of Juju’s historical significance.

You could play Moodymann records, Roy Ayers, rare grooves, breaks. It was the kind of thing where I could play sets of samples, just crazy for 45 minutes. And later on, come back with a set of something else, and I would bring the beat element.

And this is a quote from Sacred about what it was like to play there.

The key things to take away from these other parties is that they were community led and beat culture was an integral part of their musical tapestry. Sketchbook took a different approach than Juju or the clashes, but tapped into a similar spirit.

The Little Temple, 2013.

Around the time that Sketchbook moved to the Little Temple something else happened, outside the venue, that would become a pivotal moment for the local scene.

Here’s a shot of the Little Temple (now The Virgil) I took in 2013. As you can see the club stands on the corner of Santa Monica Blvd (right of this picture) and Virgil Ave (in front).

As you walk past the club’s entrance you hit the corner and find yourself under a billboard.

Corner of Santa Monica and Virgil, under the billboard.

Under the billboard is a patch of dirt. For many it’s under this billboard, on this patch of dirt, that the L.A. beat scene was born.

The infamous boombox. Photo: Dibiase

Another regular at Sketchbook was a producer from Watts named Dibiase, or Diabolikal at the time. Over the years, he’d gotten into the habit of carrying a boombox with him to parties so that he and others could play beats and freestyle outside venues, a practice that was integral to the Good Life and Project Blowed events in South Central that preceded Sketchbook in the 1990s.

People at Sketchbook would often take a break from the venue to go smoke weed outside. At The Room they’d sometimes chill in the back alley, which is where Dibiase first started bringing the boombox, or in someone’s car where they could also play their own music.

When Sketchbook moved to the Little Temple this habit of smoking weed and listening to beats outside the venue took on a whole new dimension.

Boombox session, circa 2005. Source: Twitter

Soon enough the main attraction of the night was an impromptu gathering around the boombox, outside the club, under the billboard, on the corner of two busy avenues.

Back then it wasn't easy to play music that wasn't on vinyl and so the DJs inside Sketchbook couldn't always make space for the new music those who attented were making.

But the boombox offered no such problems. And so people brought tapes of their latest work, fresh new beats from a fresh new generation of producers.

I think it was a really cool thing because it helped me open up and share. And then it helped me have confidence in myself too, you know, because I got a chance to play my stuff all the time.

Here's a quote from Georgia about her experience attending Sketchbook and the outdoor sessions in those years.

Source: Ghostnotes

B also captured this moment in time with two photos that were included in his last book, Ghostnotes. Here you can see the boombox in effect and Georgia chilling against the billboard pillars.

As a journalist I’ve learnt to be wary of trying to pin down historical moments with too much accuracy, things are always more fluid in real life than people like to admit in retrospect.

Nonetheless, during a decade of research I spoke with many people who attended Sketchbook at the Little Temple — producers, DJs, fans — and they all agree that the music played by the DJs and this practice of convening around the boombox to play and hear new shit was where many of them first began to take the idea of a local beat scene seriously.

People travelled from all over the Los Angeles area, sometimes for hours, to be there on a Tuesday and share with their peers.

The L.A. beat scene as it came to be understood in later years is made up of many experiences from people across the L.A. area, and these didn't fully coalesce into a more unified thing until a couple years later with another party. But I think it's fair to say that the spirit of the L.A. beat scene first manifested on the corner of Santa Monica and Virgil, born of the enthusiasm of a new generation and the work of those that came before them.

Everyone was so welcoming at that time. I think we all knew that there was this thing brewing. I remember how united everyone was. It was so beautiful. Everyone giving each other their moment to play beats in the car outside the club. There was a scene that was built from that.

Here's a quote from Flying Lotus, whose beats were first heard outside Sketchbook.

Top 8s And Beat Tapes 💻

The last place that helps explain Dilla's lasting influence on the L.A. beat scene is virtual. It’s the first social network to really change how we consumed and interacted with music. It was a place for friends. It was MySpace.

MySpace homepage circa 2007/8. Source: Ars Technica

It's fair to say that for a certain generation of music fans and makers, MySpace changed everything. And it did so for all sorts of scenes, including beat culture.

MySpace was the first social network to give established and aspiring musicians, producers, DJs, promoters, and fans a place to connect with others both near and far.

At the peak of its popularity in the mid 2000s it changed the rules for everyone: how to sell music, how to promote it, and, perhaps most crucially, how to define it. MySpace challenged the existing power of gatekeepers to define and decide what a scene or genre or sound was.

The days of independent versus mainstream were about to end.

I think MySpace is the big flip, it’s the post-iPod generation coming into maturity […] the listeners were left to make their own decisions, to follow their tastes and I think that’s a huge part of how [beat culture] blows up. Now it’s just a cool track, before it was asking, ‘Is this IDM, hip-hop? What is it?’

This is a quote from Ghostly's Sam Valenti that speaks to this shift in power that MySpace helped precipitate.

Another thing that made MySpace important was its impact across generations.

It wasn’t just the young kids that took to it, though they were of course the most comfortable with this new technology. It also became crucial for older heads, who weren’t as tech savvy but quickly came to understand the platform’s potential for connection and business. For example House Shoes, one of Dilla's early supporters in Detroit, told me that MySpace helped him become computer literate.

It allowed artists to blend fandom and business in one virtual interface. They could talk to fans and other artists, while selling music and booking shows.

I don’t think I really started believing in anything I was doing until I got on MySpace right when that was popping off. I had a page and eventually my music was spreading all over the place. I was seeing all the plays. People wanted to buy beats CDs, so I’d take them to Aron’s Records in Hollywood and they’d sell out.

Here's another quote from Flying Lotus about the importance of MySpace and its connection to the local spaces.

Lotus and Dibiase. Source: Dibiase

Flying Lotus is emblematic of the convergence of Aron's, Sketchbook, and MySpace in the mid 2000s, in no small part because he would soon emerge as the figure head for the beat scene that was taking shape around him.

At the same time he was also one of the few within the scene to be directly connected to some of the people that had been supporting Dilla's move to the city in the previous years, such as Stones Throw and Mochilla.

Lastly, Lotus and his peers like Samiyam and Dibiase were among a new generation who used the internet, and in particular MySpace, to evolve the concept of the beat tape away from its roots as a music industry practice and towards a release format of its own.

Trading Beats

Here's a clip of Sacred in All Ears talking about how beat tapes of Madlib would do the rounds in the pre-internet days.

Sacred was known in the scene for actually cutting tracks from beat tapes or demos and early promos to vinyl so he could play them out. Again the idea here being one of competition but also of playing the fresh new shit.

Beat tapes are relevant to this story because of how influential Dilla's own mastery of the format had become by the time the L.A. beat scene came into shape.

While largely contained as a music industry practice in the 1990s, beat tapes began to make their way outside purely business circles in the 2000s thanks in part to the growing prevalence of CDs, which made the music easier to copy.

In many of the bigger industry towns such as L.A. these beat CDs were a way for heads to get inspired and closer to their idols — Dilla but also local hero Madlib and maverick collective Sa-Ra.

As online communication became more important, beat CDs became a viable release format for upcoming producers who could make direct connections with fans and other artists. CDs were sold via MySpace with copies shipped worldwide before eventually being exchanged as zip files by fans via file lockers.

Carlos Niño, 2006. Photo: Peter Rentz.

So with all this mind I wanted to touch on a couple releases that I think help round things off and give some insight into the world that Dilla inspired and found himself associated with in the last years of his life.

Both were orchestrated by Carlos Niño — a local DJ, producer, and promoter who has always acted as a connector across scenes.

The first is a compilation titled The Sound of L.A., a snapshot of the Sketchbook moment: the boombox, the DJ sets, the digs at Aron’s.

It's an intergenerational effort with upcoming artists — Flying Lotus, Ras G, Daedalus, Kutmah, Georgia, Nobody — alongside older heads — Sa-Ra, Madlib, Cut Chemist, Sach from The Nonce — and local heroes like Sacred and Coleman.

It’s the first audio document of what would become the L.A. beat scene featuring photos of the artists taken by Coleman against the wall outside The Little Temple.

Lastly, it’s also a beat tape disguised as a compilation, something Niño had first done with his group Ammoncontact a couple years earlier, further hinting at how the format would evolve in the coming years.

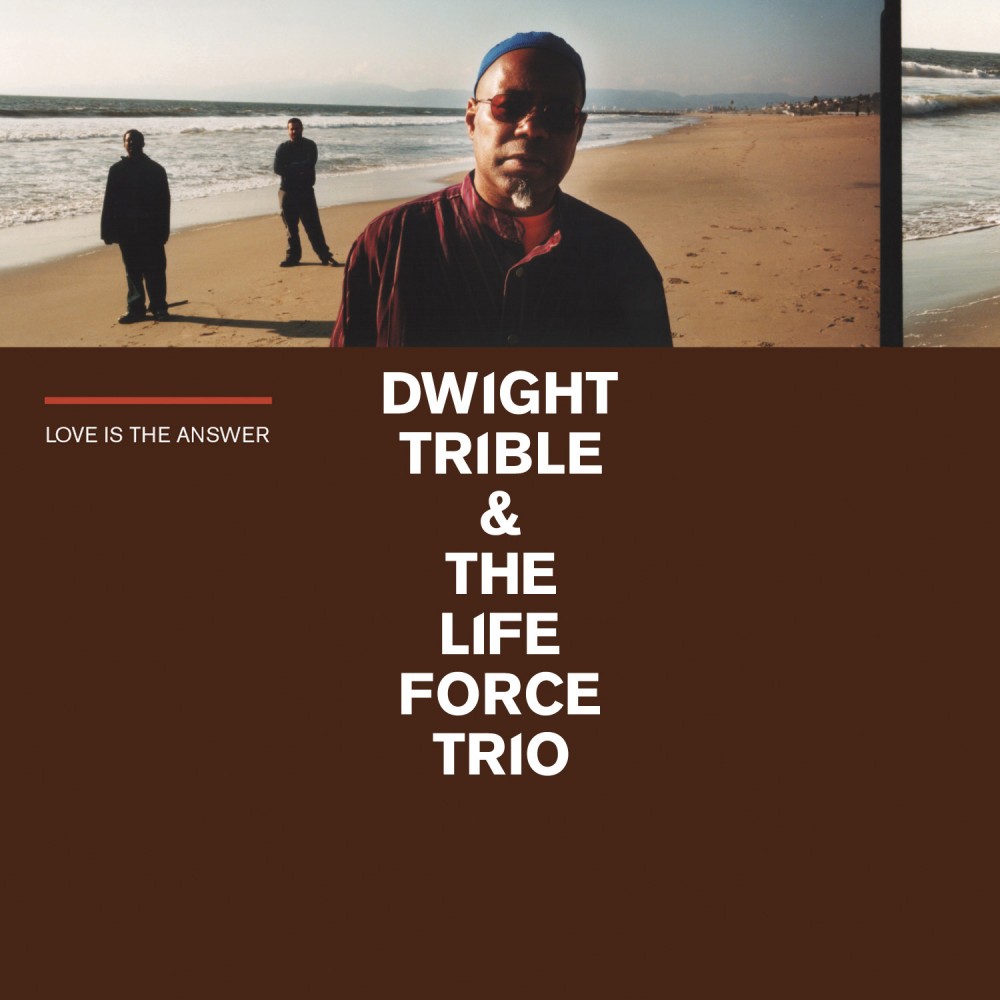

The other release is one I mentioned in passing in the book but which I’ve since come to realize is perhaps one of the more important documents of this era in how it hints at what would happen in the following decade.

It's an album that brings together L.A.'s jazz and hip-hop communities, the beat scene to be, and Dilla.

It was released as part of Carlos Niño's deal with UK label Ninja Tune and features Dwight Trible as the lead artist, one of the many local musicians Niño had connected with following his involvement in the jazz scene since his late teens.

Released in 2005 the album was neither a commercial nor critical success. But if you look at the credits, a different story emerges.

Love Is The Answer credits. Source: Discogs

In the top half you see jazz musicians old and young. Then in the middle, where it says producer, you find members of the beat scene to be - Ras G, Georgia, Coleman - alongside Sa-Ra, Madlib, and Dilla (his track is from the second volume of his unreleased instrumental series on Bling47).

Then you have scratches from Anthony Valadez, who is now one of the hosts of Morning Becomes Eclectic on KCRW, DJ Nobody on the tambourine, and John Robinson as Lil Sci on vocals (his brother is also one of the producers). Robinson gave Flying Lotus one of his first placements that same year. B+ took the album photos.

Carlos produced this album in the traditional sense, bringing together different musicians and writing some of the music and lyrics, but he also used the album to connect the new generation of producers coming out of LA to peers and predecessors in the jazz and hip-hop worlds.

In turn, the music and credits on this album connects to the next generation of jazz cats that would emerge from the city a decade later - Terrace Martin, Thundercat, Kamasi Washington, even Anderson Paak - through people like Sa-Ra who were also a great connective force.

Death and Rebirth in L.A. ☀️

In the last years of his life Dilla was an inspiration to what would become the L.A. beat scene rather than a direct participant. His untimely death would prove a catalyst of sorts for the beat scene and further cement him as the lodestar for the next generation of producers emerging from the city.

From the outside it’s easy to think that people in L.A. who we understand today as being related musically were also in direct conversation at the time, but in reality that was not always the case. L.A. is vast and as I mentioned at the start the private sphere holds more importance when it comes to relationship and scene building.

Dilla's ties to L.A., both before and after his move there, were primarily with the Stones Throw label and its own star producer: Madlib. In those years Stones Throw and Madlib were largely peripheral to what was becoming the beat scene, though as we've seen there were the odd links via people like Carlos Niño, Flying Lotus, or Mochilla.

According to B+, he once brought Dilla and Madlib to Sketchbook for a passing visit. The pair also went digging at Aron’s a few times, which is where they had the most direct interactions with those involved in what would become the beat scene.

The first meeting between Dilla and Madlib, Detroit, 2001. Source: Stones Throw

This photo shows the first time Dilla and Madlib met.

When I began writing the book I knew Dan was already working on Dilla Time so I wanted to find a way to approach Jay's importance differently. At the same time I also had to find a way to talk about Madlib without interviewing him. What I eventually realised is that they could be understood as two sides of the same coin, kindred spirits whose paths through hip-hop were mirrored and who heard in each other's music something that called to them, that said "this guy gets it."

The most common analogy is with the jazz greats that came before them. It's facile but it does speak to their historical importance: Madlib is the Sun Ra to Jay's Coltrane. Neither was easy to deal with or understand as a person, and the music reflected their respective natures and travails through the industry with unconventional singlemindedness.

In the book I positioned them as forefathers of the beat scene, both in L.A. and around the world, because of the impact their work had across different strata of hip-hop and electronic music throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s. Much of what happened next wouldn't have sounded the same without them.

Sa-Ra home studio in L.A., circa mid-2000s. Source: Back to The Lab

The other established and important L.A.-based act that had a relationship with Jay in those years, even if indirectly, was the production trio Sa-Ra composed of Shafiq Husayn, Taz Arnold, and Om'mas Keith.

Sa-Ra's sound in the early to mid 2000s was in many ways just as important as Dilla's or Madlib's in showing a different way forward for beat culture.

When I heard [these] tracks I was like, ‘Damn, he went all the way in’ [...] Soon as Taz played it, in my mind, in my heart, I was like, ‘I can’t make music where I’m at anymore, this space won’t allow me to do what I need to do'.

This is a quote from Shafiq about how hearing a Jay Dee beat CD in 1999 helped push him, and the others, towards what became Sa-Ra.

I want to show you a comment thread from Instagram started by the late Ras G that speaks to all this.

This is 2017 or 2018, Dilla month, so February, and G shared a photo of Madlib and Dilla digging and used it to recount how he got to speak to Jay that day. Then some of the Aron’s staff at the time — Pay Ray, Take, Giovanni Marks — chip in with their memories of seeing him there, the records he bought, the kindness he showed them all.

John Robinson then pops up and that triggers talks of how he connects to all this and to Flying Lotus. Alchemist chimes in about Aron’s, which was a favorite of all sorts of producers.

And then J Rocc mentions that a lot of the records used in Donuts were from Aron’s, and it’s because of this thread that I was able to reach out to J and get more details about this which made it into the book. At the time it hadn’t been public knowledge. Exile and Taz Arnold from Sa-Ra also pop in at the end.

It was Dilla’s fleeting presence in community hubs like Aron’s and his music which connects him to the birth of the beat scene in LA. But the biggest catalyst for his connection to what comes next is unfortunately his death.

Early on in my research I came to the realization that 2006 was a key year for a few reasons.

- At the start of the year Dilla passes and Aron’s closes.

- Then in the following months Flying Lotus, who would eventually become the figure head of the L.A. beat scene, and of its global expansion, begins to perform live for the first time.

- And by the end of the year, Sketchbook ends and is replaced by another weekly party dedicated to beats, Low End Theory. It was this party that would put the L.A. beat scene on the global stage.

Spaced Invaders SF flyer (L), Flying Lotus live at Low End, 2006 (R). Source: Daddy Kev.

Here you can see the flyer for a party in SF which featured one of the first live appearances by Flying Lotus and which would lead to his eventually signing to Warp Records. The photo is of Lotus performing at one of the first Low End Theory later that same year.

The first Low End Theory flyer (R). Source: Daddy Kev.

Here you can see the first flyer for Low End Theory, with a line up that connects to Sketchbook, the nascent beat scene and L.A.’s historic indie/alternative rap scene. The other flyer is from a couple years later and features a greater emphasis on sound system culture and dance music, which would become a key part of the night's aesthetic and the local and global beat scene.

Styles Upon Styles

And here's a couple quotes from Matthewdavid and Nobody, taken from All Ears, that summarize the impact Dilla had on the L.A. beat scene as it took flight in the late 2000s.

Outro (Do You!) 🙏🏻

What happens next is a story all its own, too vast to get into here.

But I wanted to share a photo that I think nicely summarizes how a new generation of beat heads took inspiration from all the things I've mentioned — Dilla, Madlib, MySpace, Sketchbook, beat tapes, hip-hop, electronic music, and each other — to create their own sonic world over the next few years.

L to R: Daedelus, Dominic Smith, Kode 9, Hudson Mohawke, Gaslamp Killer, Adam Stover, Charles Munka, Samiyam, Flying Lotus, Ras G, Theo Jemison, Martyn. Photo: B+.

This photo was taken by B+ in 2008, a couple years after Dilla’s passing. It shows a group of artists that took part in the first series of Brainfeeder shows in California. Brainfeeder was started as a collective by Flying Lotus and Samiyam around 2007 and in the following years it became a label emblematic of the beat scene's global rise, much like its founder. This photo was taken during a road trip from the LA show to the SF one.

In this one shot you see the past, present, and future of the beat scene and the realization of that search for a new type of beat that could be this generation's own:

L to R: Daedalus, Dom Smith (the A&R responsible for bringing Niño to Ninja Tune and Flying Lotus to Warp), Kode9, a Scottish producer and DJ then best known for his ties to the nascent dubstep scene, Hudson Mohawke, a kid from Glasgow that would become the other figurehead of the global beat scene, Gaslamp Killer, a local DJ cut from the same cloth as Kutmah, Adam Stover, Brainfeeder’s label manager, Charles Munka, a french artist who designed the logo as well as that of BTS, an influential local radio show, Samiyam, Flying Lotus, Ras G, Theo Jemison, a local photographer, and Martyn, a Dutch DJ and producer then best known for his ties to the drum & bass scene.

This seemingly incongruous line up, at least for the time, is what happens next: it’s no longer about a genre, but about the pursuit of an aesthetic and collective love of beat culture in its broadest sense.

And it’s no longer about just one place, but about a global network whose connections are facilitated by the internet.

You do you, I do me. And we're all gonna be able to play the same party together and hang out.

I wanted to end with a couple thoughts that hopefully tie it all together.

First is the idea I mentioned earlier of pinpointing when something starts. This tweet from journalist Mosi Reeves nicely captures why the boombox sessions at Sketchbook were important.

Low End Theory, Brainfeeder, Flying Lotus and all the people and events that came in the following years are representative of the beat scene style becoming formalized. The Sketchbook era, which also includes similar parties and communities in the UK and Europe, is that style in its raw state.

In a way it isn't unlike what happened to the formalization of Dilla's own contributions to hip-hop after his death.

As with any artistic movement there are personal politics involved, who claims what, when, and how. As a journalist it's a fine line to thread which is why I think it's important to try and center people's experiences rather than some hagiography that obscures the messy reality of how communities form and interact.

The other point is about community vs scene. This 2018 tweet from Dibiase gets to the heart of it.

This distinction is especially important with regards to what happened in the 15 or so years since the beat scene 'blew up.' The scene itself is no longer what it once was but its spirit has remained alive within the few communities that treat it as something more than just a style.

Dibiase has been one of the most important members of the original movement in this regard, actively fostering community both online and in the real world with his wife, Nas Rockwell. They're teaching kids, setting up events, working with manufacturers, and making space for others to come in and build.

This is crucial to whatever might happen next and to upholding the legacy of what came before.

Thank you!

@laurent_fintoni

laurent at spinscience dot org dot uk